Earlier this year, within my dissection of Apple’s HomePod mini smart speaker, I wrote:

I recently stumbled across a technique for cost-effectively obtaining teardown candidates, which I definitely plan to continue employing in the future (in fact, I’ve now got two more victims queued up in my office which I acquired the same way, although I’m not going to spoil the surprise by telling you about them yet).

The summary of the technique, for those of you who haven’t yet read the piece (but you should!) is that I picked up a couple of “for parts only” devices with frayed power cords on eBay for substantial discounts from the fully functional (whether brand new or used) price. One of them ended up still being fully functional; a bit of electrical tape sheltered the frayed segments from further degradation. The other went “under the knife”.

Today, I’ll showcase one of the “two more victims” I previously foreshadowed. It’s a first-generation full-size HomePod, which had the dubious “distinction” of being showcased in my “Apple’s obvious misfires” post of early 2018 by virtue both of its belated market entry and its comparatively high price versus competitors from Amazon, Google and others. The first-generation HomePod came in both black and white color schemes:

and, like its “mini” sibling announced 3+ years later, integrated a multicolor LED array-enhanced topside touch interface:

The first-generation HomePod was announced at the early-June 2017 Apple Worldwide Developer Conference (WWDC), with availability originally forecasted for December of that same year. Apple ended up not opening up order-entry until January 2018, thereby missing the all-important 2017 holiday shopping seasons, with shipments beginning a month later. It cost $349 and Apple discontinued it in March 2021.

The first-generation HomePod had a small but loyal following with folks willing to purchase even cosmetically abused used units at substantial price markups. Confession: I bought one shortly after shipments began but never got around to opening it, far from using it: I sold it on eBay in December 2021 for $529 (plus tax, with free shipping). I wish all my investments had such stellar returns! And in retrospect it was timely that I sold it when I did, because Apple surprisingly reintroduced it (with modest design changes) in January 2023 (thereby explaining all of my “first-generation qualifiers” so far in this writeup).

So, did I pay $529 for the device I’m tearing down today? Or even $349? Certainly not! Today’s patient came from another eBay “for parts only” post and set me back only $45 plus shipping and tax, for a grand total of $62.62. What was wrong with it? Here, let me show you. It initially boots up normally:

But at some point in the startup sequence, the HomePod gets stuck in an infinite “blinking” loop, alternating between a blank top and one in which both volume controls are illuminated:

Wash, rinse and repeat. And no repetition of factory reset attempts will ever result in the HomePod’s resuscitation, either. The root cause? Well, that gets us to the “design that’s flawed” claim in this post’s title. Working theories include a hardware flaw in the logic board (whose repair, you’ll soon see is “complicated”—I’m being kind with my wording—both by the difficulty in taking the device apart and getting it back together again) and an incomplete or buggy firmware update, translating, apparently and mind-bogglingly, to an unrecoverable error.

Rant over, let’s as-usual kick off the dissection with a set of outer box shots:

Top:

And bottom:

And a closeup of the lower sticker in the earlier picture:

Pull off the top and our patient is near-fully exposed, as-usual-accompanied by a 0.75″ (19.1 mm) diameter U.S. penny for size comparison purposes; the HomePod has dimensions of 6.8” high × 5.6” in diameter (170 mm × 140 mm), and weighs 5.5 lb (2.5 kg):

And here it is again, this time completely free of its prior box confines (within which remains a thin sliver of documentation paper):

The rubberized “foot”:

includes faint print documenting the FCC ID (BCG-A1649) and other minutia:

And here’s another view of the device topside, this time with the HomePod powered off (which, yes, looks like a lot like the earlier photo of it in the “extinguished” phase of the “blinking volume buttons” cycle…this time though, there’s an accompanying penny!):

That topside, post-lengthy exposure to my heat gun:

is the pathway inside:

At top is the ambient light sensor; below it and to either side are the capacitive touch volume controls. In the center is a translucent dome-plus-diffuser through which the multicolor 19-LED array below it shines, and around all of this are four hex screws. Let’s remove them next:

More applied heat to melt the glue underneath, followed by another twist o’the iSesamo:

Now let’s disconnect that flex cable:

And…voila:

The undersides of the capacitive touch sensors, which are key in illuminating the volume controls, lift right off with little adhesive resistance:

Speaking of illumination, let’s briefly revisit the PCB topside, first removing the previously mentioned dome after a short heat gun glue-softening session:

Underneath it is the aforementioned diffuser:

And underneath that is the LED array, with a closeup of the ambient light sensor as an added bonus:

Back to the PCB underside. Let’s next get that tape off the bottom of the PCB:

And finally, let’s rip the tops off the three Faraday cages:

To the left is a Cypress Semiconductor (now Infineon Technologies) CY8C4245LQI-483 PSoC 4 Programmable System-on-Chip, likely tasked with deciphering touch interface activations. And in the middle, associated with the aforementioned LED array, are five Texas Instruments TLC5971 LED drivers. Also note the three LEDs per volume control button (at top and bottom), along with lightguides that work in conjunction with the earlier mentioned reflective undersides to route illumination out the top of each capacitive touch button.

Back to our patient, with the next level of its internals now exposed by the earlier removal of the touch PCB stratum:

First off, let’s loosen those strings, which from past experience with the HomePod’s smaller sibling, I suspect also normally keeps the netting surrounding the device taut in this case:

Now for the four screws that hold the black-color plate in place:

Sliding the netting down a bit exposes a circumference set of the same rubber oval pieces that we previously saw on the HomePod mini:

Slide it down further and the six microphones also around the circumference also appear:

And, also as with the HomePod mini, the ring woven into the netting can be detached from the power cord where it enters the device:

But, unlike with the HomePod mini, the power cord itself can (unofficially) be detached, too:

Returning our attention to the top, the now-exposed next PCB “layer” pops right out:

Disconnect the wider of the two cables (the narrower one has already been disconnected on its other end):

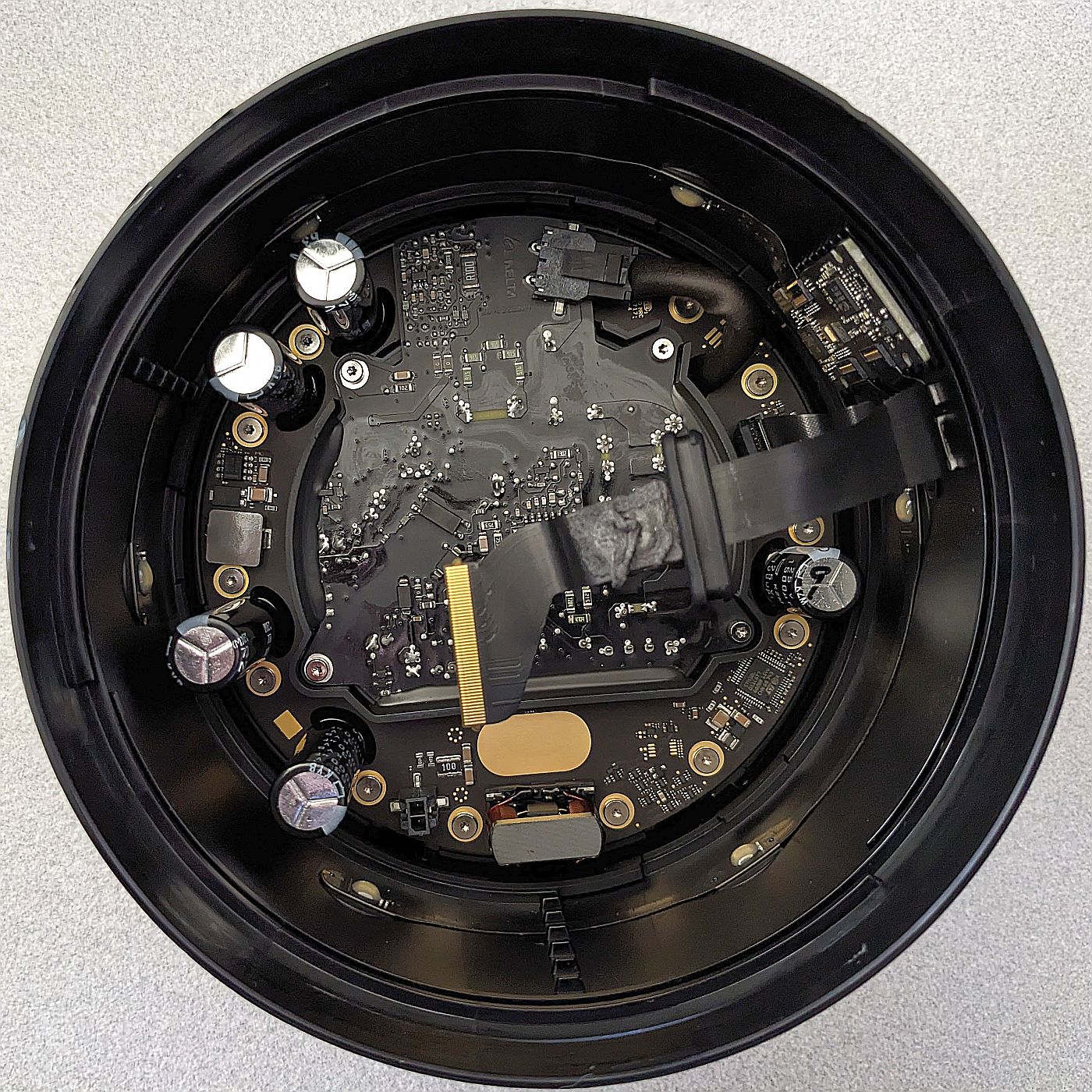

And the system PCB (named for reasons we’ll soon see) is freed from the enclosure:

Check out those heat-directing vents on the sides!

PCB topside first; let’s get off that Faraday cage:

The most notable thing here, aside from the clusters of passives indicative of sizeable chips on the other side, are three separate unpopulated IC sites in the upper two quadrants. Are they indicative of a last-minute initial design change, or a mid-life evolution?

Now for the underside and its Faraday cage (keeping in mind that heat rises, therefore rationalizing those earlier topside vents even absent obvious topside heat sources):

Next, that piece of obscuring thermal tape:

And peering closely, what do we see?

In the upper right quadrant is a 16 GByte NAND flash memory. I can’t tell from the scant markings who makes it; in iFixit’s teardown it was clearly labeled as sourced from Toshiba. Below it, in the lower left quadrant is what iFixit IDs as a power management IC co-developed by Apple and Dialog Semiconductor, the 338S00100-AZ. And in the lower right quadrant is the system’s “brains”, Apple’s A8 SoC, most commonly found in Apple’s iPhone 6 series. The HomePod’s 1 GByte of SDRAM, presumably LPDDR3 as found in other A8-based devices, isn’t seemingly implemented in standalone IC form; I’m guessing that it’s either “sandwiched” in the same multi-die package as the application processor or the flash memory.

There’s one more chip on this side that begs for attention, underneath the Faraday cage:

As with the PMIC mentioned in the previous package, it’s cryptically labeled (339S00450) and shiny-packaged. iFixit believes it to be the WiFi/Bluetooth module, likely containing a Broadcom BCM43572 IC. This functional guess seems reasonable, especially given the PCB-embedded Wi-Fi and Bluetooth antennae you may have already noticed on either side of the Faraday Cage.

Onward. Let’s get those rubber oval pieces outta there:

Yep, once again there are screws underneath. Let’s get rid of them, too:

At this point, you might logically assume that the grill surrounding the top of the HomePod, used for both sound and heat escape, would pop right off. But you’d be wrong. This particular piece is also restrained from release by some seriously intense adhesive. iFixit gave up and used a hacksaw, but following in these folks’ subsequent footsteps, I achieved the desired objective after a lengthy heat gun session (on its “high” temperature setting) around the circumference:

Woof, woof, it’s the woofer!

It’s held in place by six screws:

each surrounded by a rubber cushion:

With these impediments eliminated, the woofer lifts out of the enclosure:

and is fully freed after unclipping a connector tethering it to the audio amplifier PCB below it, which we’ll see more of shortly:

Another top view, this time shorn of its surroundings (it’s a 4”/10 cm diameter transducer):

Side:

And beefy magnet-inclusive rear:

With the woofer removed, we can now see the remaining PCBs (yes, plural) inside:

In addition to the two sandwiched PCBs inside that you can see in the previous photo, there’s another one on the side of the enclosure’s inside wall. I’ll give more detail on all three PCBs once I get more fully inside and am able to remove them:

There’s a rubber gasket, which previously sealed the enclosure-to-speaker threshold, begging for removal next:

Next to go are six more screws around the periphery:

Push the flex cable and its associated gasket through the hole:

And the upper plastic ring (of three total; hold that thought) lifts right off:

Underneath it is another (middle) ring, which this time unscrews clockwise:

Now, in addition to more clearly seeing the side-located (microphone, to break the suspense I know you’re all feeling) PCB, you can discern the two-PCB sandwich at the bottom, with the smaller power PCB fitting within the larger audio amplifier PCB below it:

To get the power PCB out requires first disconnecting the power cord connection at the top of the previous photo:

Then, remove the four screws holding the PCB in place:

And the PCB lifts right out. Here’s the topside:

And underside:

Keen-eyed readers may have already noticed that attached to the power PCB is an easily separated bracket:

Underside again, this time bracket-less. Note the connector at top mating it to the audio amplifier PCB below it and, to the left of (and below) it, markings suggesting that it may have been designed and manufactured not by Apple but by Delta Electronics:

And here’s a closeup of the bulk of the AC-to-DC conversion circuitry. Regardless of who developed this board, that’s a lovely epoxy-laden layout, even to this “digital guy’s” eyes:

Four sequential quarter-turn side views:

And finally, one last bracket-less look at the power PCB’s topside:

Next up, the audio amplifier PCB, which had circumnavigated the now-absent power PCB:

Step 1: disconnect the flex cable (whose other end point you’ll shortly see):

Step 2: remove the 14 screws symmetrically arrayed around the circumference:

With these steps completed, the PCB lifts right out:

Highlights include, on the underside, an International Rectifier (now Infineon Technologies) PowlRaudio 98-0431 audio amplifier and a Cirrus Logic CS4350 stereo DAC, both for the woofer:

along with seven evenly distributed Analog Devices SSM3515B mono Class-D 31W audio amplifiers with integrated DACs (the number “seven”, as you’ll soon see, is key).

And on the topside, there’s a STMicroelectronics STM32L051C8T7 Arm Cortex-M0-based microcontroller:

Also, don’t those towering caps look friggin’ awesome?

Now let’s revisit that already-identified microphone PCB:

Keen-eyed readers have probably already discerned the two Conexant CX20810s, each containing four channels’ worth of ADC-plus-microphone preamp combos, on the PCB. And I already mentioned the six microphones arrayed around the HomePod circumference, listening to the outside world. But what’s that also on the PCB?

It’s another microphone, this one listening to the device interior, and specifically enables fine-tuning of the woofer’s comparative (to the other transducers’) volume and other sonic characteristics.

Let’s take a closer look. Unlatch, then detach, the three flex PCB cables’ connectors, two of which are fed by the microphones’ (three each) outputs:

And after breaking the grip of a bit of adhesive, the PCB lifts right out:

By the way, that earlier-shown flex cable, the wider of the two connected to the system PCB (with the other, narrower one going to the touch PCB), splits in three directions once it gets to a point alongside the microphone PCB, to:

- The audio amplifier PCB

- The microphone PCB, and

- A shiny metal piece at the bottom of the HomePod (hold that thought)

There’s one more retaining ring to go until we’re able to start removing and peering inside the seven midrange/tweeter modules arrayed around the device’s bottom end (versus only five midrange/tweeter modules in the second-generation design, along with only four microphones, by the way). Unfortunately, it’s held in place by three tabs, each 120° away from the others, and all of which need to be depressed before the ring can be unscrewed:

These folks are apparently more dexterous than I am because they somehow managed the feat. I resorted to brute force:

In case you hadn’t already noticed where the 14 screws I’d earlier removed to get the audio amplifier PCB off ended up, there are two gold-color conductive contacts (positive and negative) on the PCB associated with the accompanying screw-fed posts on each speaker module (go back and look…I’ll wait…). Also, each module is held in place by one unique-to-it screw on the end and two shared-with-neighbor screws, one on each side.

Let’s get ‘em off:

With the screws removed, the module lifts right out:

It took enough thermal energy to deform the module’s plastic case, along with a fair bit of spent sweat equity, but I finally got the module cracked open, at least to a degree (no amount of additional heat would budge the insides, alas):

Remember that earlier mentioned “shiny metal piece at the bottom of the HomePod”? Let’s see what’s underneath it:

It’s a debug (plus, I suspect, manufacturing-line programming) port, underneath a cover:

Remove the other six midrange/tweeter modules:

Lift out a gasket between them and the bottom of the case:

But in spite of my incremental efforts, plus plenty of additional heat gun attention, I still was unable to get the rubber “foot” off. That’s some stubborn glue:

Nearly 200 pictures. Nearly 3,000 words. Aalyia is going to kill me. Anyway, enjoy. It’s been nice knowing all of you, and I hope to encounter you again in the afterlife! And please do also sound off with your questions and other thoughts in the comments.

—Brian Dipert is the Editor-in-Chief of the Edge AI and Vision Alliance, and a Senior Analyst at BDTI and Editor-in-Chief of InsideDSP, the company’s online newsletter.

Related Content